Alcohol: What Is It Really Doing to Your Body? (Part 1)

The clear, science-backed guide to what alcohol does — and how to reduce harm

Alcohol is everywhere: dinners, celebrations, stress relief, and “wind-down” rituals. It can feel relaxing and sociable, but did you know it’s a drug that affects almost every system in your body? Knowing what alcohol actually does — not just what it feels like it does — helps you make smarter choices.

Below let’s break it all down simply — and then practical, evidence-based ways to reduce harm.

Why alcohol feels relaxing (the short answer)

Alcohol (ethanol) is a central nervous system depressant. It alters brain chemistry in a few key ways:

Boosts GABA activity — GABA is the brain’s main “slow down” chemical. Alcohol enhances GABA signaling, which produces sedation and calm.

Reduces glutamate activity — glutamate excites neurons; alcohol dampens it, reducing agitation momentarily.

Increases dopamine briefly — this stimulates reward pathways and improves mood momentarily.

Raises adenosine — making you feel sleepy initially.

Those combined effects explain the immediate sense of relaxation, lowered inhibition, and the easing of social anxiety. But those same effects also cause tolerance, rebound anxiety, and disrupted sleep when used repeatedly. The later affects can also make some people even more agitated and prone to arguments or poor decisions.

Quick snapshot (fast facts)

Alcohol is ethanol — a psychoactive substance that affects virtually every organ system.

Small amounts can produce pleasant effects for many people; larger or chronic use raises risk for many diseases.

There is no universally “safe” level for all conditions — risk grows with amount and pattern of drinking.

Alcohol disrupts sleep, stresses the liver, impacts hormones, ages cells, and affects the brain’s chemistry.

What alcohol does in the body — the basics (metabolism & distribution)

After drinking, ethanol is absorbed mainly in the stomach and small intestine and travels via the bloodstream to the brain and organs.

The liver metabolizes most alcohol using alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzymes; toxic acetaldehyde is an intermediate (this causes flushing and cellular stress).

Some alcohol and metabolites circulate systemically before they are cleared; chronic intake leads to repeated exposures and cumulative effects.

Alcohol & the brain

Short-term effects

Impaired judgment, slower reaction time, memory lapses and, at high doses, blackouts (failure to form new memories).

Mood changes: euphoria then often depressed, or irritated, mood as alcohol wears off.

Long-term effects

Repeated heavy drinking can cause structural and functional brain changes — reduced volume in the hippocampus and frontal lobes is commonly reported, which affects memory, planning, and impulse control.

Increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia with long-term heavy use (pattern and dose dependent). Heavy use can mean different things for different people.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) changes brain reward circuits, making quitting harder.

Special risks

Adolescents and young adults are especially vulnerable because the brain is still developing; alcohol can impair maturation of critical brain circuits.

Alcohol & sleep — the hidden cost

Fall asleep faster: Alcohol’s sedative effects can help you fall asleep more quickly.

Fragmented sleep: Alcohol reduces REM sleep and causes more awakenings later in the night, producing non-restorative sleep.

Creates dependence for sleep: Using alcohol as a sleep aid worsens sleep architecture over time and can lead to rebound insomnia when stopping.

Net effect: fast sleep onset help but poorer quality sleep and daytime tiredness.

Endocrine & hormones: alcohol’s hidden manipulations

Cortisol and stress axis: Alcohol acutely raises stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline), even though it can feel calming; chronic use dysregulates the HPA axis (think “adrenal fatigue”)

Sex hormones: Alcohol can alter estrogen and testosterone levels. In women, alcohol may increase circulating estrogens; in men chronic heavy use lowers testosterone and can impair fertility.

Thyroid and metabolic hormones: Chronic heavy drinking can perturb thyroid function and metabolic hormone balance; overall metabolic regulation worsens.

These hormone shifts help explain mood changes, changes in fat distribution, menstrual disruption, and reproductive effects.

Liver & metabolic health

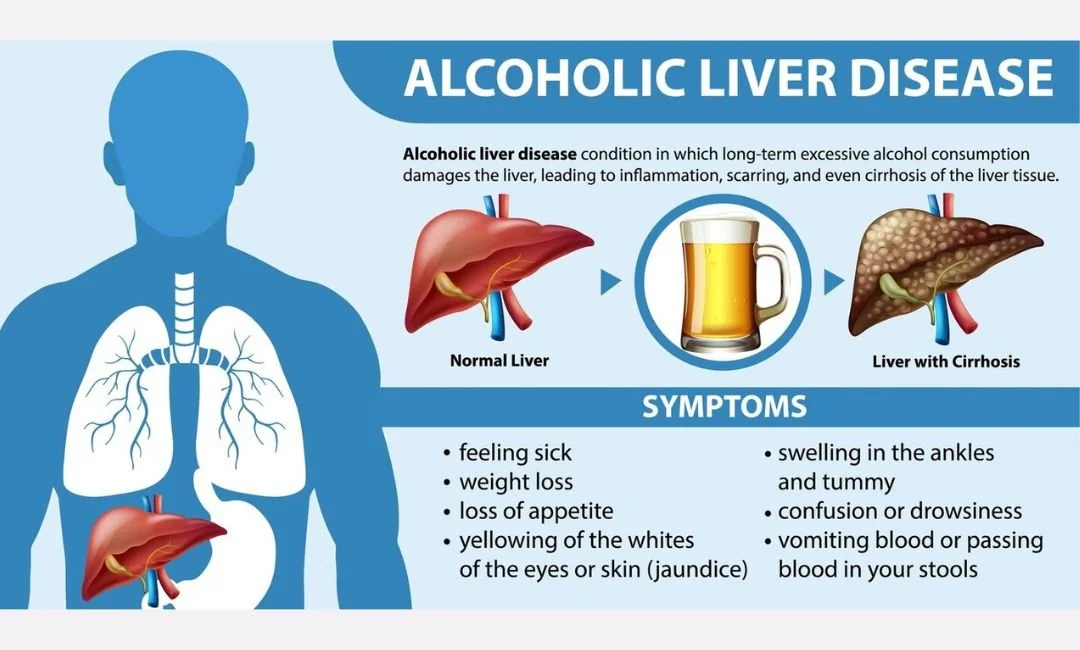

The liver is the primary organ harmed by alcohol. Stages of alcohol-related liver disease include fatty liver → alcoholic hepatitis → fibrosis → cirrhosis.

Alcohol increases liver fat (steatosis) and oxidative stress. Even moderate drinking can contribute to fatty liver in some people, especially combined with obesity or metabolic syndrome.

Alcoholic liver disease is a major cause of morbidity worldwide; the liver’s detox systems are overwhelmed by chronic alcohol metabolism and acetaldehyde exposure.

Alcohol contributes to belly fat through a mix of calorie load, hormonal changes, and fat storage patterns — and it’s not just about “empty calories.”

Heart, blood vessels & metabolism

Blood pressure: Alcohol can raise blood pressure acutely, and heavy consumption is linked to chronic hypertension.

Arrhythmias: Binge drinking is a known trigger for atrial fibrillation (“holiday heart syndrome”).

Cardiometabolic effects: Some older studies suggested light drinking might have cardioprotective associations, but more rigorous analyses show risk tradeoffs (and any benefit is small and not universal). Drinking increases risks of cardiomyopathy and stroke.

…to be continued in Part 2