Insulin Resistance: The Deep Dive

Insulin Resistance: What It Is, What Causes It, and How to Turn It Around

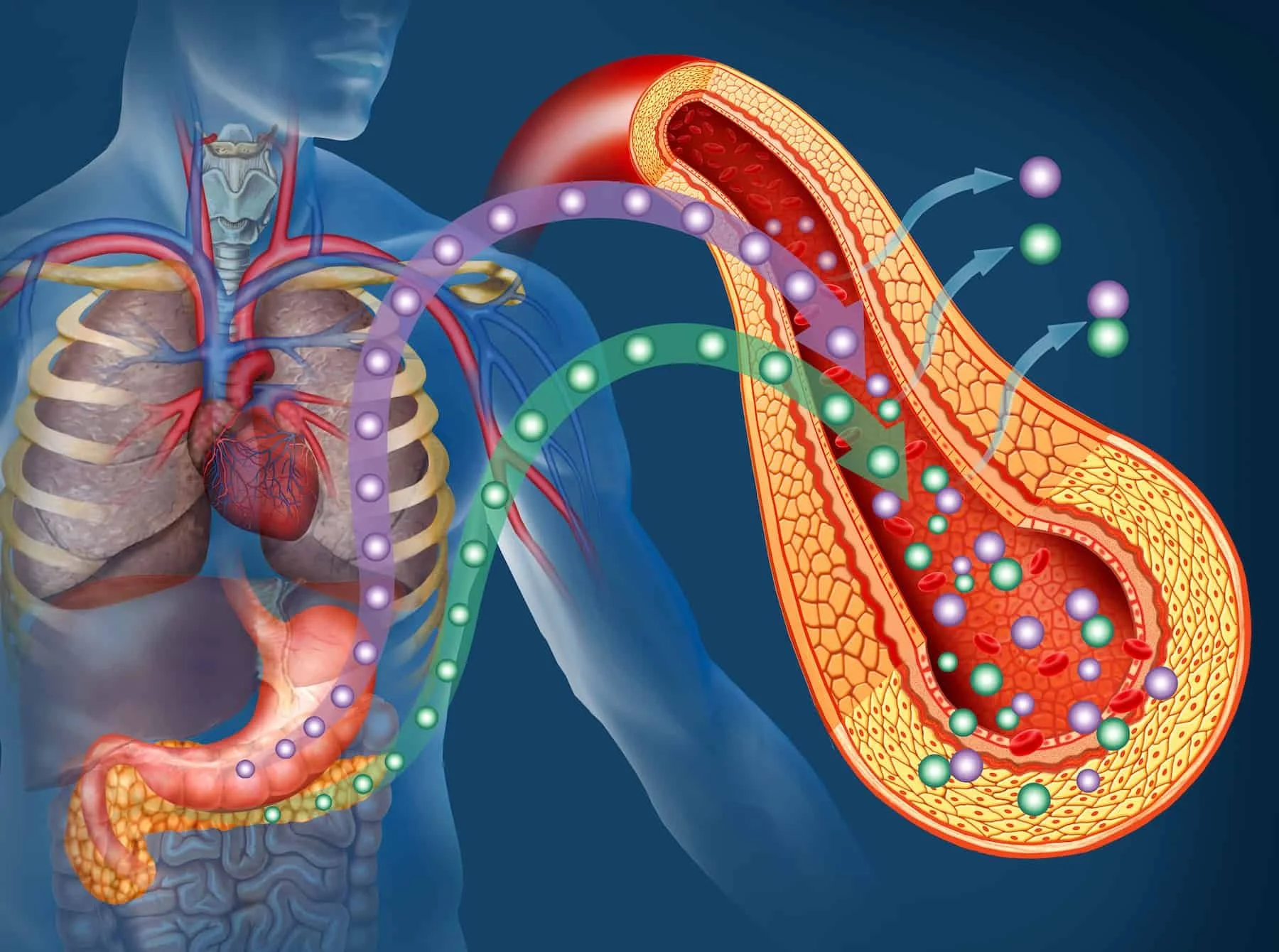

Insulin resistance (IR) means your cells stop responding normally to insulin — the hormone that tells cells to take up glucose from the blood.

Over time, IR forces the pancreas to produce more insulin to keep blood sugar normal. Persistent insulin resistance is a major driver of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, and it also raises risk for fatty liver, cardiovascular disease, and chronic inflammation.

Below I unpack the main drivers, what the science says, and practical, evidence-based steps you can take to reverse it.

Sugar and excess refined carbohydrates contribute to insulin resistance

Acute effect: High blood-sugar spikes after sugary or refined-carbs force large insulin releases. Repeated spikes lead to blunted cellular responses and higher baseline insulin needs.

Weight & fat distribution: Excess calories from sugary drinks and refined carbs promote visceral fat (belly fat).

Metabolic inflammation: Fructose and refined sugar can increase liver fat and inflammation, impairing insulin signaling in the liver and muscle.

Bottom line: frequent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and refined carbohydrates is strongly associated with higher insulin levels, visceral adiposity, and future diabetes risk.

Making Insulin Resistance Easy to Understand

Okay — imagine your body’s insulin like a “delivery truck” that carries sugar (glucose) from your blood into your cells to be used for energy.

When you eat refined carbs (like candy, soda, white bread), your blood sugar rises really fast. Your body sends out lots of delivery trucks (insulin) to bring all that sugar into the cells.

If this happens over and over, your cells start saying:

“Whoa, there are too many trucks showing up all the time! We’re going to stop answering the door so often.”

That’s called insulin resistance — your cells don’t respond as well to insulin anymore.

Now your body has to send even more trucks just to get the sugar into your cells. Over time, that’s hard on your pancreas (the “truck factory”) and can lead to higher blood sugar and health problems.

It’s like someone sending you 100 pizza deliveries every single day that eventually, you just stop opening the door — even when you’re hungry.

Processed & ultra-processed foods: it’s not just about calories or fat

Ultra-processed foods (UPF) — most packaged snacks, sweetened cereals, sodas, instant meals, and many restaurant “value” items — are not just calorie-dense. They carry several properties that increase insulin resistance risk:

High added sugar, refined starches, and industrial fats → metabolic stressors.

Low fiber and low nutrient density → poor satiety, overeating, and worse post-prandial glucose responses.

Food additives & emulsifiers that may alter the gut microbiome and intestinal permeability, promoting low-grade inflammation.

Linked epidemiologically to higher rates of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

Large prospective studies and systematic reviews have found that higher UPF consumption is associated with greater incidence of type 2 diabetes and markers of insulin resistance — even after adjusting for calories and body weight in many analyses. This suggests UPFs drive metabolic harm beyond simple excess calories.

Circadian rhythm, sunlight, vitamin D — the light piece of the IR puzzle

Your body’s metabolic machinery is wired to a daily clock: insulin secretion, glucose tolerance, and fat metabolism vary across the day. Disruptions to circadian rhythm (shift work, late nights, chronic social jetlag, screen time) impair glucose tolerance and raise insulin resistance risk.

Clock misalignment (e.g., eating late, working nights) changes how muscle and liver use glucose and worsens insulin sensitivity.

Sunlight & vitamin D: daytime bright light exposure helps synchronize circadian rhythms. Low vitamin D status is associated with poorer insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in many observational studies.

While vitamin D supplementation trials show mixed benefits, the observational link and biologic plausibility are strong enough to recommend sensible sun exposure and checking vitamin D levels if someone is at risk.

Practical micro-steps: prioritize morning daylight (15–30 minutes), avoid bright screens at night and/or get bluelight blocking glasses, and time your meals to daytime hours when possible - no late night snacking.

Exercise is one of the most powerful tools to improve insulin sensitivity

Exercise increases glucose uptake into skeletal muscle through insulin-dependent and insulin-independent pathways (notably GLUT4 translocation). Both aerobic and resistance training improve insulin sensitivity — and even a single bout of exercise can temporarily increase glucose uptake for 24–72 hours. That’s some good news!

Mechanisms: improved mitochondrial function, increased capillary density, enhanced GLUT4 expression/translocation, reductions in visceral fat, and lowered systemic inflammation.

Dose: regular moderate aerobic exercise (150 min/week) plus 2–3 sessions of resistance training is a strong evidence-based prescription; higher-intensity interval training can produce faster metabolic gains in many people.

How these causes interact (the vicious cycle)

Processed foods, irregular sleep/light exposure, and inactivity often cluster together in modern lifestyles.

They amplify each other:

Eating UPFs late at night → larger glucose spikes when circadian glucose tolerance is low.

Night shift or screen nights → poorer food choices and less activity the next day, as well as, throwing off the body’s natural circadian rhythm.

Sedentary behavior → fewer glucose disposal opportunities for muscle → higher insulin exposure.

Breaking one link (e.g., adding daily walks and swapping out UPFs) often helps the others—so small wins compound.

In the next blog post we’ll dive a little deeper into reversing IR if you, or someone you love, is dealing with these issues.